The ambiguous revolution of 1989

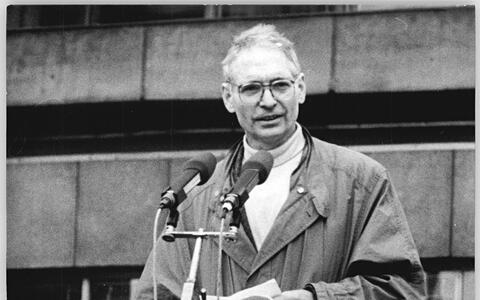

Professor Jens Reich, doctor, molecular biologist, civil rights activist, researcher and ombudsman at the MDC

Jens Reich was one of the speakers at the demonstration in Berlin’s Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989.

The word Wende has enjoyed an unstoppable career in everyday usage because it offers a concise and smooth way of referring to the time before and the time after 1990: “before the Wende” and “after the Wende.” Many contemporaries of the time, myself included, find this annoying because the word, which was being used before 1989 in the political parlance of the Federal Republic of the Kohl era, was co-opted by SED leaders fighting for political survival (especially Egon Krenz) to create the illusion of a change in direction that would save the system. The people wanted absolutely nothing to do with that kind of Wende, and began (even before Christa Wolf’s speech on November 4) calling any comrade who asserted these peaceful reforms a Wendehals [meaning “turncoat” or “opportunist”]. Coincidentally, ornithologists named the Wendehals (a bird of the woodpecker family) their bird of the year in 1988, and this provided the caricaturist at Die Zeit newspaper with inspiration for a highly amusing caricature. It shows a patchily feathered bird sitting in a jagged-edged hole in the Berlin Wall. The bird bears the unmistakable features of Egon Krenz. The caption reads: “Wendehals, bird of the year.”

Since then, activists who were involved in the upheaval, as well as journalists and contemporary historians, have been trying to encourage everyone to replace the term Wende with the unwieldy construction “peaceful revolution” as the factually appropriate label. This expression, too, has an unmistakably persuasive intent. The popular uprising was definitely not “peaceful” in the sense of being “passive.” “Non-violent” would be the correct adjective, and to this day theorists still disagree about whether or not it was actually a revolution. Anyone who went to school in the GDR and continued to read newspapers after that will understand this key term of Marxist theory (with the paradigmatic example of the great French Revolution of 1789) as referring to a violent (!) and radical change in the fundamental relations of property and production and the corresponding state structure and therefore the entire superstructure – in other words, the social and cultural circumstances of a country’s population. Anyone who belonged to the GDR population will doubtless intuitively confirm that something like this occurred in 1989, regardless of how any political scientist would interpret it.

If one stays with the Marxist doctrine of the state, however, one will perhaps have to agree to the term “counterrevolution” because the popular movement’s intuitive goal and achieved result were definitely not the establishment of a new social order, but rather the re-establishment of a previous order, perhaps approximate to the Weimar system. That it would eventually lead to adopting the entire social order of the Federal Republic – and not just its prosperity – had perhaps been in the minds of some people from the outset, but it later troubled them and they wished they could have retained some familiar elements. This is the only way I can explain the deep sigh that I often heard after 1990, when all this became reality: “This isn’t why we had the revolution!”

“The fall of the Wall” also lacks clarity as a descriptor of the actual event. The Wall didn’t fall, metaphorically speaking, as a result of the action of the people (as in Joshua 6:20, “As soon as the people heard the sound of the trumpet, the people shouted a great shout, and the wall fell down flat”). Rather, we owe the opening of the border on November 9 to Günter Schabowski (“effective immediately, without delay…”) and border guard Harald Jäger (“We’re opening the floodgates now!”). The revolutionary people behaved well and promised: “We’ll come back!” They had their identity cards stamped for the supposed permanent right to leave, and went to inspect the West.

We are the and/or one people

Conflicting tendencies are especially prevalent among those who came of age politically in the East: At the time, most people were vehemently in favor of a quick reunification; today, many claim it was imposed by the elite in Bonn.

Equally ambiguous are the two famous slogans, primarily heard in Leipzig, of Wir sind das Volk (“We are the people”) and, weeks later, Wir sind ein Volk (“We are one people”). The first slogan can be very energetically chanted by an anonymous crowd, with strong emphasis on the all-unifying “we,” and it suggests the subsequent cry of “… and not you up there, you SED fat cats and bloc-party puppets!” The second slogan doesn’t provide the same kind of metrical rhythm because it won’t accommodate emphasis on the word “one,” which was the variation on the first slogan. Instead, the second slogan lumbers along syncopatedly. If one chants it as energetically as the first, the unstressed “one” crumbles in the vicinity of “any” and leaves behind the unarticulated notion that, even back then, the “united people” tended toward a division between those who wanted to become immediately and unconditionally part of the Federal Republic, and those who were hesitant or even hostile to joining.

This ambiguity was from the outset an inherent part of the events that overturned the system. During those weeks, the contradictory terminological pairs of “top–bottom,” “East–West,” “revolution–change of direction,” and “liberal–illiberal” were all simultaneously available and effective, but a decision was postponed and is still outstanding today. In fact, after a seemingly calm adjournment that lasted for a decade, the contradictions are now – 30 years later – emerging once again as standard-bearers of opposing political views.

While those advocating and acting for change in 1989 chanted Wir sind ein Volk to demand the opening of the Wall, the demolition of borders, freedom, and the opportunity to go out “into the open,” those who are once again chanting Wir sind das Volk (not “one people” this time) today want new borders and exclusion, the re-establishment of control, and none of the changes that the global removal of borders brings with it. With a majority of the population vehemently and publicly rejecting movements such as the AfD and Pegida, it is also clear that people want to suppress the ambiguous tendencies in their own political thinking.

Conflicting tendencies are especially prevalent among those who came of age politically in the East: At the time, most people were vehemently in favor of a quick reunification; today, many claim it was imposed by the elite in Bonn. Likewise, most people today support taking in refugees, but immediately follow that by saying that the imminent global tide of refugees must be curtailed so as to avoid jeopardizing the fragile balance between freedom and security. Here, a lack of security is about both the impositions that are emerging at the global level, and the social and political conflicts that have broken out internally.

New crises, new polarization

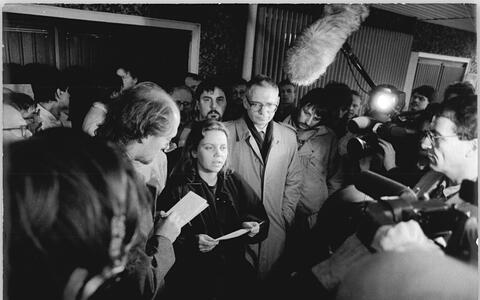

Jens Reich and Margitta Hinze at a press conference in 1990. Photo: Federal Archives

Ten years ago – on the 20th anniversary of the autumn of ’89 – one could have believed, as I did, that the more or less successful revolution was now in the past, that the fat lady had sung, and all the words and stories had been recorded in countless books, newspaper articles, and audio and video documentaries. It was thought that the non-violent popular uprising had re-established civil liberties and human rights in the East, and had also formed a society whose mentality and economy were slowly approaching the example set by the Federal Republic in the West. The formation and realization of political will mainly happened through the parties, which compiled civil society’s wishes and demands, checked them to see if they could be implemented and win a majority, and then, as appropriate, put them into effect through parliament and the government. However, the question of whether this democracy would actually remain stable if faced with severe social crises went unanswered.

In the years since, we have indeed experienced numerous crises – some brought in from the outside, others home-grown. And we are very far from having any fundamental solutions: The bearers of the political mandate to “run on sight,” are attempting unsatisfying compromises and stalling by pushing the essential decisions into the future.

The political mood among the electorate is currently tending toward one of two barely reconcilable poles: One is liberal, supportive of human rights and civil liberties, globally minded, immigration-friendly, welcoming of reforms, and positively disposed to Europe; the other is authoritarian, nationalistic, critical of migration, and in favor of exclusion and control. One group believes that the state’s main task is to guarantee the freedom of the individual, while the other believes that establishing security and order is paramount. In terms of the environmental question that will decide our future, one group believes that our current way of life, which is a danger to the biosphere in its entirety, must radically change – often without realizing how severe the consequences for their own lives will be. The other side denies the crisis, thinks that we cannot influence it, or that if one occurred, we could solve it with technological inventions and measures – through “growth” – with no need to give up anything.

The mental divide between these two poles is most pronounced in the territory of the former GDR. So pronounced, in fact, that it is becoming difficult to form functioning state governments and, in some cases, municipal political administrations.

The emergence of the mental divide

Looking back on the epochal year that was 1989, I can say that the divide was already present and clearly visible back then. Not in the politically active, citizens’ movement groups, which were almost exclusively left or liberal or both. And not among those who would later become non-voters and in whom the authoritarian tendency was covertly present. Yet both tendencies attended the big demonstrations, and they were also the catalyst for the shift from Wir sind das Volk in late October to Wir sind ein Volk at the end of the year.

Even in the New Forum, in which I was an activist, I often heard political beliefs (about matters such as abortion, divorce law, or education) that would absolutely belong in the Pegida or AfD camp today. That autumn, such differences of opinion were just “minor inconsistencies” that did not distract us from our common aim of abolishing the repressive state and establishing rights to freedom. Later, they moved very much into focus, and for the New Forum, whose supporters were regionally very diverse and spread across all social strata, they were one of the main reasons why the movement collapsed.

The founding members of the New Forum were often accused of writing a proclamation that was not a political agenda, but a naïvely romantic wish-list. It’s an accurate description and as one of the authors, I admit that this was our explicit intention. }A few weeks before the New Forum was officially founded, Bärbel Bohley invited me to a preparatory discussion (Erika Drees, Katja Havemann, and Rolf Henrich were also there), during which we wanted to discuss, as we had often done before, taking political action. We agreed on a manifesto that would include very specific elements: It was to be a call to form a legal association (the Decree on the Founding and Activity of Associations of 1975 was cited word for word) for safe, open civil dialogue about urgent and concrete matters in current social developments, with discussion goals that could be supported by anyone with a reflective mind, even if they were not immediately realistic (as a kind of short-term vision), without the prior polarizing fixation on a political allegiance and with no well-worn politspeak (therefore written in understandable German), and with the full name, place of residence, and profession of the signatories, who should come from all over the Republic (not just from Berlin and other big cities) – framed as an appeal for support or involvement from people, ideally as many women as possible, “from all walks of life, professions, parties, and groups.”

A revolution with a platform ticket

Mass rally at Berlin Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989, when several hundreds of thousands people demonstrated for a democratic renewal of the GDR.

Just two months before “the fall of the Wall,” on the weekend of September 9 and 10, 1989, a group of 30 people gathered in Grünheide, just outside Berlin, in the bungalow that had belonged to the deceased dissident Robert Havemann, and discussed the manifesto at length. A few of us had prepared draft texts, which were debated and finalized. Then we typed up a page on the typewriter, with a few carbon copies, and arranged to meet in early December to discuss how those in citizens’ movement had responded.0} Bärbel Bohley and Katja Havemann took the copies we had produced and announced that they would pass them on to the GDR and Western press agencies for publication.

The date of the “follow-up” – early December, as I said – shows that we hadn’t the slightest idea of the degree to which the paper would mobilize people, and of the events that were to follow. The signatories lived all over the GDR, and in the ensuing weeks they were all “overrun” by a rush of people who were declaring solidarity with the manifesto and, in some cases, asking to immediately apply to join the association. Their numbers quickly grew throughout the Republic – in two weeks they had exceeded several thousand, by early October they had reached tens of thousands, and by the end of the year they had reached the 200,000 mark.

The unexpected avalanche of mobilization was triggered by a number of factors that we were only partially aware of at the time of writing the text. One major factor was lawyer Rolf Heinrich’s absurd idea – given that the authorities wielded absolute control – to legally apply to set up an association. It is reminiscent of Lenin’s adage that German revolutionaries will buy a platform ticket before storming a train station. Indeed, we know from many statements that those of a cautious disposition were motivated to sign and circulate when we explained our legal intentions to them.

Another factor was the emphatically non-political way in which the proclamation was formulated, with the text only occasionally hinting at its subversive nature (e.g., “We want to be protected from violence without having to endure a state of spies and flunkeys.”) The text is also free from any explicit attacks on the repressive regime. As for the word “socialism” – the reform and realization of which was the topic of papers published at the same time by the other oppositional citizens’ movements – we decided after heated discussion not to include it, as it was too discredited. The paper also refrains from criticizing the ruling SED – at the time, many people still believed that critically minded young party members could join the momentous dialogue.

Ultimately, the carefully formulated harmlessness of the text is probably what convinced a great many hesitant people to come out of their shells and join a growing movement. They had good reason to be fearful and cautious. The memory of the bloody events of June 17 were just as vivid as those of the war that the Soviet army waged against Budapest in the autumn of 1956, and of the Prague occupation of 1968. Many people had experienced first-hand the civil war that the army waged against the people in Poland during the 1980s, while others had seen reports about it on Western television. What’s more, the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 4, 1989, was an ever-present, threatening cloud in the political sky.

Yesterday leading the change, today the losers

And yet here, too, the whole ambiguity of the disruptive chapter was apparent. Just a few months after being the driving force behind the events, we found ourselves at the last Volkskammer elections, democratically defeated, at the children’s table of the future political leaders – as the opposition.

A revolutionary situation arises – as another of Lenin’s wise sayings goes – when those at the top can no longer rule as they used to, and those at the bottom no longer want to be ruled in that way. This can-no-longer was obviously the gloomy mood both in the Central Committee at Werderscher Markt and, for a short time, in the Kremlin – which is most astonishing, given that it had political tools and immense military power at the ready. Gorbachev’s opponents in the Politburo would just have had to engineer his demise a few months earlier and resurrect the Brezhnev Doctrine for the economic and political decline of the Eastern Bloc to take a very different course. The Wall would probably still have come down, but would the GDR and the Eastern Bloc have collapsed politically?

A radical change of direction is possible!

DDR, Berlin, 04.11.1989, Protestdemonstration, gegen Gewalt und für verfassungsmäßige Rechte, Presse-, Meinungs- und Versammlungsfreiheit, Protest gegen Übergriffe von Volkspolizei und Stasi gegen Demonstranten am 7. Oktober, organisiert von Theaterleuten und Kulturschaffenden, Palast der Republik, Berlin

But that is all just mere speculation. What is clear, however, is what the population was no longer willing to endure. Even at the time, though, it was much less clear what those “at the bottom” in the Eastern Bloc and the GDR wanted instead. Today, the growing disunity among the people inhabiting these countries is bringing to light the full ambiguity of those past events. Thirty years on, one can no longer describe the events that occurred around 1989 as a true epochal change toward a stable democratic constitution in all 15 new and 5 old nation-states that (re-)emerged in the wake of the upheaval in the Eastern Bloc. Much as in the former GDR, many of these states are witnessing the emergence of authoritarian, neo-nationalist, and xenophobic trends, and are exhibiting similar tendencies to Western democracies. Today, we are further than ever away from being able to say that history is over and the West has won. The global confrontation of the Cold War has transformed worldwide into a jumble of local confrontations that are anything but cold.

While these movements – whose focus on the present and the past often make them reactionary – dominate our attention, the maturing crisis of the future is being suppressed. This is not just about the threat of a warmer climate and all the ensuing consequences. We are also facing a possible collapse of our planet’s entire biosphere as we overwhelm the Earth with our excessive consumption and unbridled accumulation of precarious end-products.

As a biologist, I say that preventing this collapse demands a fundamental, radical change in every life-sustaining activity in which Homo sapiens engages. A great many people doubt that this is achievable. But if 1989 taught us anything, it is that a sudden, unexpected, radical change of direction is within the realms of the possible when “theory becomes a material force” because “it has gripped the masses.” I do not wish to see this hope revealed as a mere illusion.

This article originally appeared in German in Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, 11/2019, www.blaetter.de."

© picture-alliance / dpa /Zentralbild