Millions for cancer research

Thomas Blankenstein

The European Research Council (ERC) has announced it will support Professor Thomas Blankenstein to the tune of €2.5 million over five years. This year the ERC is awarding Advanced Grants to a total of 158 scientists across Europe.

“I am glad to announce a new round of ERC grants that will back cutting-edge, exploratory research, set to help Europe and the world to be better equipped for what the future may hold. That’s the role of blue sky research”, says Professor Mauro Ferrari, the President of the ERC in an official statement on March 31, 2020. “These senior research stars will cut new ground in a broad range of fields, including the area of health. I wish them all the best in this endeavour and, at this time of crisis, let me pay tribute to the heroic and invaluable work of the scientific community as a whole.”

In Blankenstein’s research group, scientists at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin study specialized cells of the immune system called T cells. With his new research project Blankenstein wants to find out how T cells respond when their specific receptors detect a new antigen on a cancer cell. This line of research promises to identify more effective immunotherapy strategies for treating cancer.

Difficult conditions for research on immunosurveillance

Scientists have been discussing the immunosurveillance theory for some 50 years. The Australian virologist Sir Frank MacFarlane Burnet suspected in 1970 that the immune system is constantly on the lookout for cancer cells in order to eliminate them. According to his hypothesis, certain properties presented on the surface of cancer cells enable T cells to recognize tumors. “There is no doubt that T cells often detect cancer by recognizing these antigens and destroy tumor cells,” Blankenstein says. He assumes that there is a form of immunosurveillance that is triggered by virus-induced cancer, but says that “in spontaneously growing tumors we don’t yet know if this actually starts a program of destruction in the T cells.”

Blankenstein has been working for years on immune therapies against cancer. "In our new research project we want to find out how a T cell reacts as soon as it recognizes a tumor antigen," says Blankenstein. He wants to know: "Does the T cell then induce the destruction of the cancer cells? Does this mean that immunosurveillance is also possible for cancer that develops spontaneously in the body?

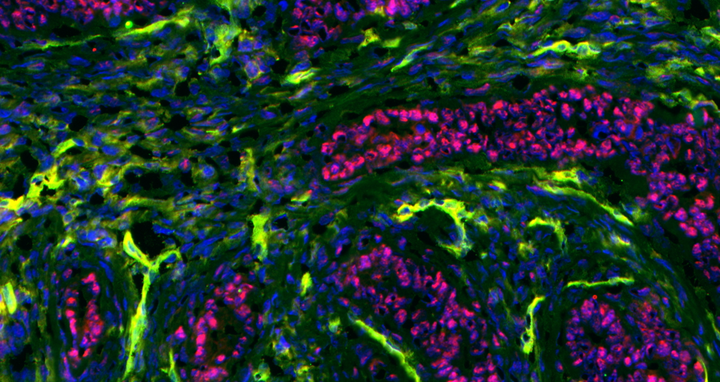

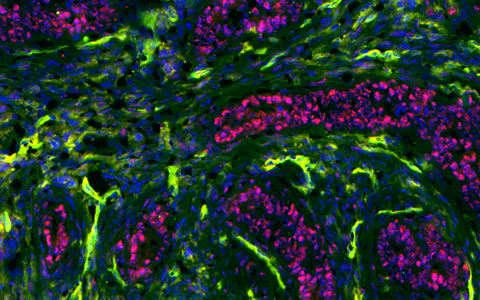

Cancer consists not only of cancer cells (red), but also of stroma cells including immune cells (green).

To answer these questions, Blankenstein suggests a new research approach. Conventional research models, he says, have always a hitch. Scientists often study immunosurveillance in mice by using, for example, chemical substances to induce tumor growth in a normal cell. He explains the problem: “Either such research models fail to reflect tumor growth in humans or we cannot clearly say whether, and how, T cell behavior actually affects the tumor.”

A promising new research approach

What Blankenstein will do differently is transplant tumors into the mice. He has developed two mouse models for this purpose, but first he had to overcome several hurdles. The biggest problem, Blankenstein explains, is that an invasive procedure such as a transplant always causes inflammations in the mouse. This means it is difficult to investigate how T cells behave when cancer arises, because one doesn’t know if the T cells are just responding to the tumor antigen as a result of the interventional procedure on the tissue. Blankenstein’s research group has succeeded in reestablishing non inflammatory conditions that mimic sporadic cancer development in humans. He has not yet published his research models, which he will use for the first time in the new project. They allow him not only to regulate the presentation of tumor antigens, but also to measure T cells’ behavior to cancer recognition.

The project could change the way we look at immunosurveillance in spontaneous tumor growth.

Blankenstein plans to hire additional postdocs and PhD students to support his new research project. He says: “The project could change the way we look at immunosurveillance in spontaneous tumor growth.”

About ERC Grants

The funding program of the European Research Council (ERC) is one of the most important in Europe. Since 2009, ERC Advanced Grants have covered all scientific disciplines. Recipients are awarded up to €2.5 million for a period of five years.

Further information

Downloads

Portrait of Thomas Blankenstein, © David Ausserhofer, MDC

Cancer consists not only of cancer cells (red), but also of stroma cells including immune cells (green). © Blankenstein Lab, MDC

Press contacts

Professor Thomas Blankenstein

Head of the Research Group on Molecular Immunology and Gene Therapy

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

Head of the Institute for Immunology

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin

tblanke@mdc-berlin.de

Christina Anders

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 (0)30 9406 2118

christina.anders@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.