Don’t retreat to splendid isolation

Potsdamer Platz was sprawled out before them, vast and desolate. Overground trains weren’t stopping there anymore, and the underground station was also closed. It was the morning of August 13, 1961. Ruptured paving and piled-up ramparts already formed a line where, just a short while later, the Berlin Wall would stand, separating the east and west of the city. Jens Reich and a friend were discussing what they should do. Try to get out somewhere, maybe across the allotment gardens on the edge? Leave everyone behind? No, their personal ties were too important. And anyway, as they told themselves: “This barrier can’t last forever.”

But last it did, shaping the life of physician, molecular biologist, and bioethicist Jens Reich. Reich was one of the key figures of the civil rights movement in the GDR, co-founding the citizens’ movement Neues Forum (New Forum).

- Stations of Jens Reich’s life

On March 26, 1939, Jens Reich is born in Göttingen as the son of a physician and therapeutic gymnast, and grows up in Halberstadt.

1956 – 1962:

Studies medicine and molecular biology at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and then works as a junior physician at the Salvator hospital in Halberstadt.1964 – 1968:

Completes specialist training in biochemistry at Friedrich Schiller University Jena.1964:

Receives his doctorate in human medicine (Dr. med.) at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 1976 second doctorate (Dr. sc.).1968 – 1990:

Scientist at the Central Institute of Molecular Biology (ZIM) of the GDR Academy of Sciences.1969/1970:

Co-founds the Freitagskreis (Friday Circle) in which some 30 young intellectuals debate culture, philosophy, and literature. Because of the conditions in the GDR, these discussions quickly become political in nature and critical of the system. Many Friday Circle members go on to join the opposition. The circle has been systematically surveilled by the Ministry for State Security since the 1980s.1974/75 und 1979/80:

Research stays at the Institute of Cell Biophysics of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Pushchino near Moscow.1980:

Appointed Professor of Biomathematics and Department Head at the ZIM.1984:

Because of his advocacy for freedom and civil rights, his research group in Berlin-Buch is dissolved and he is demoted to research assistant. He is also banned from traveling abroad.starting 1985:

Participates in working groups and opposition initiatives such as those associated with the Gethsemane Church, the East Berlin Environment Library, and Physicians for Social Responsibility.1988:

Publishes critical analyses of the GDR system in the journal “Lettre International” under the pseudonym “Thomas Asperger.”1989:

Co-authors the manifesto “Aufbruch 89 – Neues Forum” and is a founding member of the Neues Forum (New Forum).4. November:

Gives a speech at the Alexanderplatz demonstration.1990:

March until October: Member of the Alliance 90/The Greens group in the GDR’s first and only freely elected parliament.October - December:

Member of the German Bundestag1990-1992:

Chairman of the GDR section of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW).1991:

Awarded the Theodor Heuss Prize, on behalf of many civil rights activists in the GDR.1991 – 1992:

Visiting professor at Harvard University and at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg.1992 – 2004:

Head of the Bioinformatics Department at the Max Delbrück Center.1993:

Awarded the Anna Krüger Prize for his good and understandable scholarly language.until 2011:

Coordinates joint research project on systems biology of Max Delbrück center, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and Heidelberg University.1994:

Nominated by The Greens to stand as an independent candidate for president of Germany.Participated in the German Human Genome Project.

1996:

Awarded the Lorenz Oken Medal of the Association of German Natural Scientists and Medical Doctors.1997:

Founding member of the "Willy Brandt Circle" in Berlin, initiated by Günter Grass and Egon Bahr1998:

Awarded the Urania-Medaille1998 – 2004:

Professor of Bioinformatics at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.2000:

Awarded the National Prize of the German National Foundation.2001 – 2012:

Member of the National Ethics Council and its successor organization, the German Ethics Council.2009:

Awarded the Carl-Friedrich-von-Weizsäcker-Preis of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and Stifterverband.Until 2022:

Research Ombudsman at the Max Delbrück Center.Until now:

Member of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.Since 1962, Jens Reich has been married to the physician Dr. Eva Reich and has two daughters, a son, and numerous grandchildren.

Like a caged bird

At the age of 17, Jens Reich moved to the East German capital from Halberstadt to study medicine at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Thanks to the then still-open sector boundaries, he was able to become acquainted with the science and culture of two systems: productions by Gustaf Gründgens, Bertolt Brecht and Walter Felsenstein, French courses at the Maison de France, lectures by Robert Havemann. When the Berlin Wall went up, he suddenly felt like “a caged bird.” In 1966, he found out just how tightly secured his cage was. Reich was offered a six-month research fellowship with a Max Planck Institute in the West. He was promptly summoned to the dean’s office where the party secretary dismissively rejected his request. Reich was not even allowed to respond to the offer.

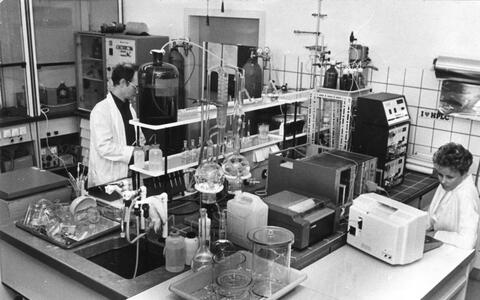

Biochemical lab at the Central Institute for Molecular Biology.

He managed to create his own sphere of freedom. In 1968, he joined the newly founded Computing Center at the Central Institute of Molecular Biology (ZIM) of the GDR Academy of Sciences in Berlin-Buch. Due to a lack of chemicals and technologies in experimental biochemistry, he turned instead to theory and developed mathematical models for the energy metabolism of living cells. He escaped “dull daily life” in the GDR from 1969/70, through the Freitagskreis (Friday Circle). This was a group of around 30 young intellectuals who would meet every week to debate culture, philosophy, and literature. These discussions quickly became political in nature. Many Friday Circle members went on to join the opposition.

Thermos flasks full of mercury

The Academy of Sciences in Berlin-Buch was a saving grace for a long time. “There was still some awareness of the outside world,” said Reich. But only the so-called travel cadre had the privilege of presenting their ideas to the wider world. And as the West was modeling biological systems with ever faster computers and greater storage capability rather than with differential equations, the intellectual bonds between East and West were being wrenched apart. “Our science was reduced to tilling a tame little plot of land,” explained Reich. So why did he stay in the GDR? “That’s the kind of person I am. . . . You would have had to drive me away.”

Following his research stays at the Institute of Cell Biophysics of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Pushchino near Moscow in the 1970s, Reich became concerned with the impending economic and ecological collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. “The valley of the Oka, a huge river, had turned into a dumping ground,” he recounted. “The children would go out to play in the forest and come back with thermos jugs full of mercury!” At this time the Aral Sea was gradually drying up, the Soviet army was occupying Afghanistan, and everyone was talking about zinc coffins. “It was obvious that this country was headed for disaster,” he added.

Young people were running away

Reich had close friends within the Soviet Union, with people from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. “Solidarność dissidents stayed at our apartment on their way to the West, for example,” said Reich. It was no longer enough to dutifully pursue one's own science and merely long for reforms. The intensive discussions made this clear to him.

He looked for ways to bring about meaningful change and spoke, for example, at the Gethsemane Church in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district about the ecological crisis in the GDR and the militarization of school education. This did not go unnoticed by the Stasi. In 1984, his research group in Buch was dissolved and he was demoted to research assistant. “They thought they could discipline me that way. It had the opposite effect. But all the other things, the dissident groups, were more interesting and lively,” he said. Especially when Gorbachev came to power in Moscow in 1985.

More pressing was the fear that Reich’s own family might be breaking apart. One daughter had already left, the other two children were on the same path. “The outlook is bleak for any country whose young people are running away,” he said. The first paragraph of the founding manifesto Aufbruch 89 – Neues Forum makes reference to this emigration: “In our country communication between state and society is obviously troubled. Proof of this is the widespread dissatisfaction that has led people to retreat into a private niche or to emigrate in large numbers. In other areas of the world such massive flights are the result of deprivation, hunger, and violence. This is by no means the case in our country.” Jens Reich co-authored this manifesto and was one of the first signatories.

Taking the constitution literally

Instead of “sitting quietly in a snail's shell with antennae tucked in,” the activists took the GDR constitution at its word. Bärbel Bohley and Jutta Seidel applied on September 19, 1989, for official recognition under the law governing private associations. The authorities rejected their applications up until November. But the manifesto spread like wildfire and 200,000 people signed it before the year was out. The demand to grant official recognition to the New Forum became one of the rallying cries at the nationwide protests. “It was the naive reference to our legal intentions and the Constitution of the GDR that prompted hundreds of thousands of the hitherto silent, disgruntled majority across the country to join the mainstream movement of regular citizens and bring about the collapse of the heavily armed regime,” said Jens Reich.

On November 4, 1989, he stood on a truck bed on Alexanderplatz as a speaker for the New Forum and looked uneasily out at the restive mass of people. Practically everyone in Berlin who could walk was afoot, and hundreds of thousands joined the demonstration, not afraid at all. ‟Along the edge of the road a group of mimes even acted the role of the Politburo and waved their hands in the fashion of gerontocratic leaders,” he continued. While giving his speech, he did not initially notice the cheerful atmosphere. “At the front stood undercover Stasi operatives. They gave us a nasty heckling and made you feel as though something was weighing heavily on your heart.”

A completely new world

The peaceful revolution of 1989 was the second life-altering experience for Jens Reich. He assisted in preparations for German reunification as a member of the Alliance 90/The Greens group in the GDR’s only freely elected parliament. After a year he withdrew from politics – apart from when he stood as an independent candidate for president of Germany – and returned to the world of research, where he helped shape another breakthrough: the decoding of human DNA as part of the Human Genome Project. He also tackled the bioethical issues related to this undertaking as a member of the German Ethics Council from 2001 to 2012.

Prof. Jens Reich

At the Max Delbrück Center, he headed a medical genome research group from 1992 until his retirement in 2004. The Buch campus and the center were at the heart of his entire professional life. He witnessed the transformation – from a closed community where groups usually grew old together, and gossip thrived to a scientific system that was above all oriented to the outside world. Until 2022, one could see Jens Reich striding across campus several times a week with thick file folders and books under his arms. He was Ombudsman for Good Scientific Practice, was involved in the animal welfare efforts and encouraged debate on bioethical issues.

And what about today? “We are living in a completely new world. As a natural scientist, I can take positions on important issues concerning the future. Though I don’t run the risk of being arrested and jailed, I must still remain determined,” said Jens Reich. It would be too easy to relinquish to others the necessary task of giving public commentary on policy issues, particularly in areas that require the painstakingly acquired expertise of scientists. “It is our responsibility, without hysterical alarm, but also without quiet resignation, to inform the public of the dangerous crisis that our planet faces and to help find ways to reduce the threat.“

Text: Jana Schlütter

A version of this text was published in March 2019, on Jens Reich's 80th birthday. We have updated it and added quotes from a speech on the 30th anniversary of the founding of the New Forum.

Further information